By MICHAEL MCCAUGHAN

If you are looking for the “Innovation” piece of the FDA Safety & Innovation Act, one section of the new law jumps out: Section 902 – “Breakthrough Therapies.”

The provision creates a new section of the FD&C Act, and inserts it directly before the “Fast Track” and Accelerated Approval sections also included in FDASIA. That symbolic position indicates the intent: something that happens even earlier in drug development than the existing FDA mechanisms.

The actual steps towards hyper-acceleration, however, are not well-defined: the legislation lists a series of steps FDA “may take,” most of which boil down to enhanced communication about trial design to complete development as quickly as possible.

The best description of the pathway may have been delivered by Center for Drug Evaluation & Research Director Janet Woodcock during hearings on FDASIA: she said that the “breakthrough” designation would encourage the sponsor and the agency to call “all hands on deck” to rethink the development plan rather than plow through a traditional Phase 1-2-3 process.

FDA is directed to flesh out its ideas for applying the pathway in guidance, which is due to be published in 18 months. However, the pathway is effective as of the signing of the law (July 9), and so sponsors can begin to seek the designation right away.

If history is any guide, the new designation will be attractive to start-up biotech companies, eager to claim a new badge to attract investment. That can and does have an impact on drug development: after all, without investment, early stage ideas wouldn’t get very far.

But what will the actual impact be on the pace of drug development through the pipeline?

That is a much tougher question to answer.

One place to start is with the background of how “Breakthrough” became law. Understanding the pedigree of the provision is a good way to understand its likely impact.

“Breakthrough” emerged from conversations within the oncology community, including FDA, patient organizations, academics and industry. And it fed into an appetite for pro-innovation reforms on Capitol Hill. Those two elements help explain how “Breakthrough” became law, despite being a relatively late entrant into the mix of proposals that ended up being adopted by FDASIA.

In that sense, the first “breakthrough” already happened: a new section of the FD&C Act moved rapidly and smoothly into law. Whatever else the provision means, that makes it an important case study for sponsors interested in pursuing legislative changes in future user fee cycles.

“Home Run” Trial Design Meets Progressive Approval

The “Breakthrough” designation came into being thanks in part to a convergence of two separate policy debates:

- Advocacy from the biotechnology industry for a new approval model (often referred to as “progressive approval”) that would potentially revolutionize the drug approval process; and

- A drive to rethink the standard development pathway for targeted cancer drugs that seem to promise astonishing efficacy.

The push for Progressive Approval came from the Biotechnology Industry Organization, which unveiled a proposal to allow FDA to approve drugs after Phase II in exceptional circumstances. (“BIO’s “Big Ideas” Include Expanding FDA’s Mission, Allowing “Progressive Approval”” — “The Pink Sheet” DAILY, Jun. 28, 2011)

In BIO’s original framing, progressive approval would have been a shortcut to allow marketing to begin before typical pivotal studies are completed; the idea was offered in very rough form with the clear acknowlegement that issues like alignment with Accelerated Approval and ideas to allow approval based on a “weight of the evidence” standard would need to be worked out.

BIO worked with Sen. Kay Hagan (D-N.C.) to begin to flesh out that proposal as legislation. However, it became clear relatively quickly that it would be very difficult to build consensus behind anything that sounded like (and was intended to be) a fundamental change in the FDA standards for evidence – no matter how strong the desire to support and encourage medical innovation.

So Hagan’s bill morphed into provisions to codify and clarify the relationship between Accelerated Approval and Fast Track, an important nuance in the regulatory process to be sure, but not exactly the type of profound change originally advocated by BIO.

The policy discussion in oncology, on the other hand, began with somewhat more modest ambitions: essentially as a call from one of FDA’s top reviewer managers for industry to believe its own hype.

Office of Hematology & Oncology Products Director Richard Pazdur, framed the issue in a presentation to an Institute of Medicine conference on cancer policy in late 2010. “If one has truly a home run, why not just take this drug to an early randomized study looking at a realistic and large effect?” he said.

“If one has a response rate of 60-70%, it is ridiculous to look at an improvement in overall survival of only two months,” Pazdur continued. Instead, “one should really be focusing on a home run here and looking at a hazard ratio of perhaps .5 or an 80% improvement in overall survival rather than meager improvement in overall survival.”

The key message from Pazdur is that sponsors should not follow a “cookie-cutter” approach to development of targeted therapies, which he characterized as gathering an initial response rate from a Phase I/II study and then running a 100+ patient single-arm study to tease out some response rates to support an accelerated approval. (“Swing for the Fences: FDA’s Top Cancer Drug Official Urges “Home Run” Trial Designs for Targeted Therapies” — The RPM Report, January 2011)

Roots in Friends of Cancer Research

That call to action was answered through a project sponsored by the Friends of Cancer Research and Brookings as part of their annual Conference of Clinical Research in November 2011.

The “Breakthrough” designation arose out of a working group that included CDER’s Janet Woodcock focused on the topic of “Development Paths for New Drugs with Large Treatment Effects Seen Early.![]() ”

”

The resulting white paper focuses primarily on a proposed trial design “to demonstrate a large treatment effect in a small number of patients,” meaning about 120-150 patients. The intent would be to allow approval if indeed the effect size is dramatic, or to serve as a screening study for an expanded Phase III trial if the effect isn’t as large as expected.

The actual trial proposal, however, was less interesting than Woodcock’s comments (and a separate addendum written by FDA) that offer the beginnings of a description of the “Breakthrough” pathway. Woodcock commented that, in general, when a drug shows dramatic response rates in hard to treat settings like metastatic solid tumors, “you should stop and think” about the next steps to ensure that the development proceeds as rapidly as possible.

A Genentech executive also commented on the white paper, in part because the recent hyper-fast approval of the company’s targeted melanoma therapy Zelboraf prompted the discussion. Zelboraf moved from IND to approval in near record time. However, some cancer treatment advocates argued that the trials were needlessly large and had control arms that left too many patients needlessly exposed to obviously inferior therapy. (“Speedy Zelboraf Approval: “The Fastest Development Program at Genentech”” — The RPM Report, November 2011)

Genentech’s comment on the draft was that the proposed study design likely would not have sped up the development path, but it would have reduced the trial size (and cost).

Those two reactions helped frame the ultimately successful push for legislation. As enacted, the new “Breakthrough” designation essentially creates a framework for intense engagement with FDA leadership as early as Phase I, and explicitly envisions a development path tha minimizes the exposure of control group patients to less effective therapies.

“Breakthrough” On the Hill

The proposal outlined in the November White Paper became the basis of legislation introduced in late March by Sens. Bennet (D-Colo.), Hatch (R-Utah), and Burr (R-N.C.).

The bipartisan support was critical to enactment in the context of FDASIA, but the trio was also an interesting and important mix of sponsors. Bennet spoke during the November FOCR conference and has been a staunch ally of the organization. Colorado is not as robust a biomedical innovation center as California or Massachussets, but it does have a growing community of biotech firms, including an Amgen campus that is a legacy of that firm’s acquisition of Synergen.

Hatch, of course, has an extensive history of FDA legislation and his support lends weight to any proposal involving the regulatory system.

Burr also has long record of legislative work on FDA, especially in the context of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act. His support was noteworthy given the role of North Carolina’s junior senator (Hagan) in the early work on Progessive Approval.

There were also two key endorsements of the bill from outside groups. The National Venture Capital Association explicitly supported the proposal, and therefore helped assure that “Breakthrough” was picked up by the “pro-Innovation” side of the FDA legislative efforts.

But FDA also implicitly endorsed it. Woodcock never specifically advocated the statutory change in her testimony, but her participation in the working group and an appearance at another Capitol Hill event hosted by FOCR offered a clear show of support.

In contrast, agency officials raised more explicit public concerns about proposals that would change the approval standard like “Progressive Approval.”

Once adopted into the legislation, “Breakthrough” move through the legislative process without incident, a clear example of how FD&C Act changes can be non-controversial.

Faster Than Fast-Track

Whether the legislative breakthrough will lead to more therapeutic breakthroughs is another question entirely.

To qualify for “Breakthrough” status, a sponsor must apply for a designation to FDA. The criteria are broad: the drug must be intended for a serious or lifethreatening disease and be supported by “preliminary clinical evidence [that] indicates that the drug may demonstrate substantial improvement over existing therapies on one or more clinically significant endpoints, such as substantial treatment effects observed early in clinical development.”

During the FOCR workshop in November, Woodcock cited the example of metastatic solid tumors, where no approved agents show much effect. If a therapy showed a significant response rate in Phase I, she argued, the next step should be for an “all-hands-on-deck” discussion of how best to expedite the development.

The law, however, does not in any way limit the conditions for which “Breakthrough” status applies. While FOCR and FDA clearly see a role in certain oncology settings, there is no reason not to expect sponsors of diseases for other serious conditions to seek a “Breakthrough” designation.

But what, exactly, does a “Breakthrough” designation mean?

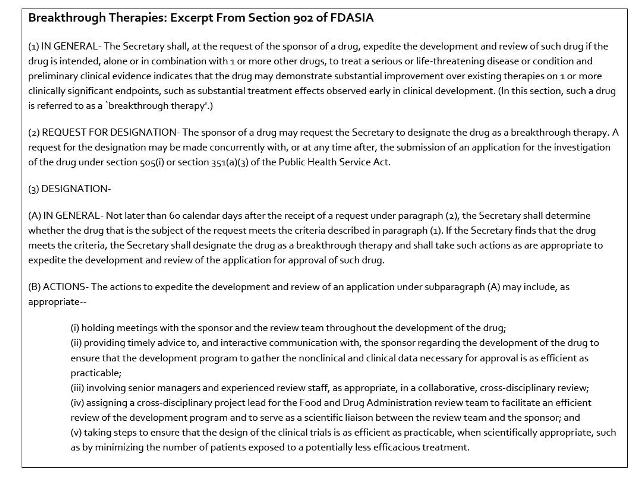

There, the language is decidedly vague. The legislation lists a series of steps FDA “may take,” most of which boil down to enhanced communication over trial design to complete development as quickly as possible. (See Exhibit 1.)

Exhibit 1

“Breakthrough” Defined

Source: FDA Safety & Innovation Act

Bullet (v) probably best captures the twin goals articulared in the FOCR working paper, the idea of taking a “time out” to consider alternatives to the traditional Phase 1-2-3 approach—and to avoid exposing more patients than necessary to older therapies that the “Breakthrough” may supplant. The provision directs the agency to take “steps to ensure that the design of the clinical trials is as efficient as practicable, when scientifically appropriate, such as by minimizing the number of patients exposed to a potentially less efficacious treatment.”

FDA is directed to flesh out its thinking on “Breakthrough” via guidance, to be published by January 2014.

An early step in defining the pathway is expected to come (appropriately enough) via a working group presentation during the 2012 Conference on Clinical Research. A panel discussion is set for November 14. (See Exhibit 2.)

Exhibit 2

Developing Standards for Breakthrough Therapy Designation

In follow-up to the 2011 session, Development Paths for New Drugs with Large Effects Seen Early, The Advancing Breakthrough Therapies for Patients Act was proposed to expedite development of new, potential “breakthrough” drugs or treatments that show dramatic responses in early phase studies. In this regulatory pathway, once a promising new drug candidate is designated as a “Breakthrough Therapy”, the FDA and sponsor would collaborate to determine the best path forward to abbreviate the traditional three-phase approach to drug development. While potential abbreviated and condensed trial designs were proposed in the 2011 session, this year’s panel will focus on defining the criteria necessary to define a product as a Breakthrough Therapy.

Panelists:

- Dr. Charles Sawyers, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center

- Dr. Daniel Haber, Massachusetts General Hospital

- Dr. Percy Ivy, NCI

- FDA: Dr. Robert Temple, FDA

- Dr. Sandra Horning, Genentech

- Ms. Wendy Selig, Melanoma Research Alliance

As a practical matter, however, the ground rules are likely to be set via the agency’s response to the first designation requests.

Clearly, oncology will be a primary focus for the new pathway, since it had its roots in that field. But the pathway is in no way limited to oncology sponsors—and that may quickly lead to the first real tests of exactly how big an impact “Breakthrough” will have on drug development.

FDA is likely to receive numerous requests for designation from sponsors hoping for a “home run” of their own: a new designation to attract investment to finish development of a project in an unsettled area of science.

In many cases, there may be an implied pressure on FDA to demonstrate that it considers a given disease as serious as cancer—and the nuance that the validation of molecular targets in oncology is much more advanced than in other diseases may be lost. FDA may have no choice but to dilute the value of the “Breakthrough” designation by applying it in settings where clinical success is much less likely to follow. Alternatively, FDA may have no choice but to withhold “Breakthrough” status except in cases where clinical success is already a foregone conclusion. In either case, the designation would end up having minimal impact on drug development overall.

Even in oncology, FDA faces a dilemma with the new pathway. There is always a challenge for the agency in designating something as high priority and then facing criticism if it is unable to approve the drug once the final data are in. That dynamic is heightened by the terminology: if FDA has declared a drug a “breakthrough,” non-approval seems especially hard to explain.

In addition, the agency may be skittish about the implied endorsed of an investigational agent, which seems like to encourage patients to seek enrollment in studies of the “breakthrough” agent. That could disrupt other ongoing clinical trials—and of course potentially expose more patients to a drug that turns out to have unexpected adverse effects.

A Recipe for Future Reforms – And A Different Approach By NORD

Only time will tell whether the “Breakthrough” designation actually translates into more breakthrough drug launches. But as biopharma companies ponder ideas for more radical reforms to the regulatory model (i.e., adaptive licenses or revisiting Progressive Approval), the pathway to enactment of “Breakthrough” is instructive.

The key steps appeared to be the ability of one prominent and effective advocacy group (the Friends of Cancer Research) to build the idea from the ground up. The development of the proposal involved stakeholders from across the oncology sector, including patient organizations, clinicians, trialists, industry—and, crucially, FDA.

To achieve enactment, FOCR found the right allies—in part by allowing the pathway to be open to any disease. The support of the venture capital association was critical in positioning Breakthrough as a pro-innovation component of FDASIA – another “I” element to balance the many provisions under the “S” for Safety component.

But biopharma companies should also consider the possibility that a legislative approach can backfire. Given the role of the agency and especially CDER Director Woodcock in defining the new pathway, there was every reason to believe the agency would be willing to do everything the statute directs anyway, without the law. By creating a formal designation process open to all comers, “Breakthrough” could end up slowing down some of the projects FDA would otherwise accelerate – after all, time spent reviewing designation requestions is time not spent working directly with sponsors to accelerated their development programs.

In that context, it is instructive to consider how other pro-innovation provisions in FDASIA were crafted.

In the context of rare diseases, there are two sections of the new act that are directly intended to encourage innovation in rare disease: a new priority review voucher program to reward sponsors of pediatric rare diseases (Section 908), and a new consultation process to allow input by rare disease specialists directly into the application review process (Section 903).

Both sections were enacted without the active support of the National Organization for Rare Disorders.

It’s not the NORD is opposed to the new programs, but rather the organization focused its activities differently. NORD worked through the PDUFA consultation process to secure funding to fully staff FDA’s existing rare disease staff within the Center for Drug Evaluation & Research. NORD has also been working with the agency to develop a consultation process administratively, and did not see legislation as necessary to accomplish that goal.

Instead, NORD focused its FDASIA lobbying around ensuring that all the provisions appropriately considered the issues related to rare disease. For instance, the codification of Accelerated Approval in FDASIA requires FDA to issue a guidance within a year, and states that guidance shall “specifically consider” issues for Orphan-designated products and “also consider any unique issues associated with very rare diseases.” That language was sought by NORD to address the challenges of using AA in rare disease programs.

Overall, there are about 60 specific references to “rare diseases” in the law, reflecting the efforts to assure that those issues are considering in many different regulatory contexts.

But NORD has generally been happy to work directly with FDA on issues related to the review process, rather than seeking legislation to change standards for orphan drugs. And NORD believes that approach has been working well: after all, the creation of a Rare Disease Staff within the drug center was an administrative action by FDA in 2010 that did not come via Congressional direction.

So biopharma sponsors may want to keep one eye on how FDA’s handling of drugs to treat rare diseases evolves at the same time that the agency is implementing the new “Breakthrough” pathway: that could provide useful guidance on whether legislative changes or administrative reforms are the more effective route to accelerate drug development in the long run.