FDA & Regulatory Policy

Homologous Recombination Deficiency Harmonization Project

FDA

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or FDA, is an agency of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Originally founded in 1906 to ensure the safety and purity of American food and pharmaceuticals, the agency has expanded to regulate prescription and over-the-counter drugs, vaccines, medical devices, veterinary products, dietary supplements, cosmetics, and tobacco products. Each year, the FDA regulates over $1 trillion worth of consumer goods–about 25% of all U.S. consumer expenditures. The FDA employs over 10,000 full-time employees and is organized into agencies charged with the regulation of different products, including the Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, the Center for Veterinary Medicine, and the Center for Devices and Radiological Health.

CDER

Within the FDA, theCenter for Drug Evaluation and Research, or CDER, is responsible for monitoring the development, production, and labeling of drugs to ensure their safety and efficacy. CDER relies on the results ofclinical trialsto determine the benefits and possible harms associated with new treatments.Regulators at CDER are also committed to making promising new treatments available to patients as efficiently as possible, a goal that is achieved through the use ofexpedited approval mechanisms.

CBER

TheCenter for Biologics Evaluation and Research, or CBER, is similar to CDER but monitorsbiological medical productsrather than drugs. Where drugs are created through chemical synthesis, biological medical products, or biologics, are created through biological processes. These products include vaccines, human cells, tissues, and cellular and tissue-based products, some medical devices, and a range of other articles used to diagnose and treat illness. In the same way that CDER tests, analyzes, and approves new drugs, CBER tests new biologics. For the sake of simplicity, this page will focus on the new drug approval process.

The Drug Approval Process

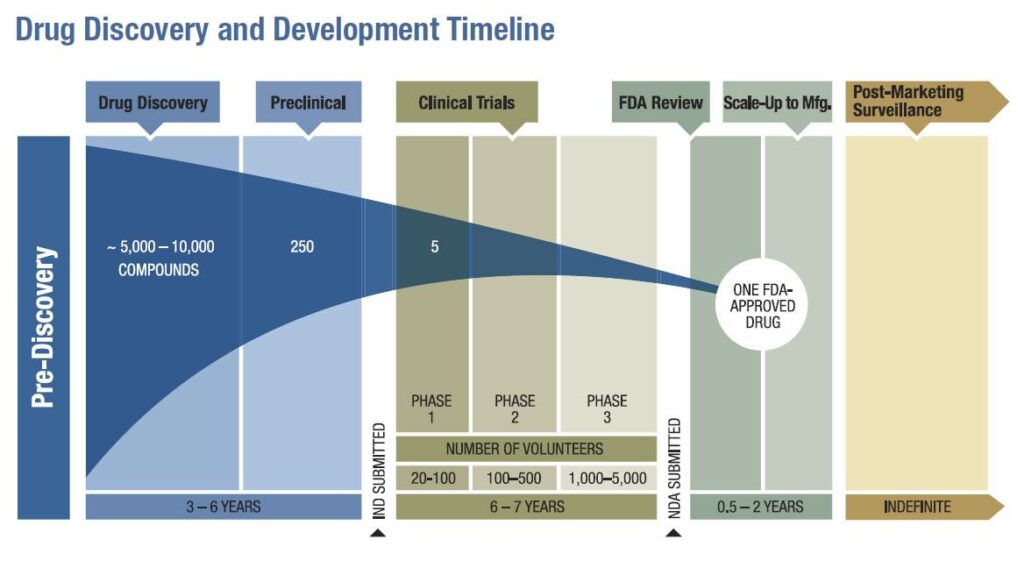

The drug approval process relies on a public-private partnership between CDER and drug sponsors–the organizations (primarily pharmaceutical and biotech companies) responsible for developing new drugs.The process is rigorous–only a small portion of the drugs submitted to CDER are approved. Regulators and sponsors work together to ensure that the process is as efficient as possible. Even so, it takes an estimated 8.5 years on average for a sponsor to bring a drug from early laboratory discovery to approval for human use. Throughout this process, a sponsor must reach out to CDER for clinical trial design guidance, analysis of results, and permission to conduct and escalate human testing. Sponsors submitting new drugs are also required to payuser feesin order to ensure that FDA has sufficient resources to operate efficiently. FDA identifiestwelve stepsin the complete development and review collaboration.

- Early Development and Preclinical Testing: Drug development begins with laboratory research into chemical interactions, often building on preliminary work from academic groups, government institutions such as the National Institutes of Health, and prior development studies. Once a sponsor has developed a chemical that they believe could be used as a treatment for disease, they must conduct animal testing in order to demonstrate that the chemical is safe. The FDA will not allow human testing of substances that have not been shown to be reasonably safe in animals.

- Investigational New Drug Application: Before a sponsor can begin clinical trials, they must submit an application to the FDA describing their pre-clinical trials, the drug’s composition and manufacturing, and the their plan for human clinical testing. This is called an Investigational New Drug Application, or IND.

- Phase 1 Clinical Testing: If the FDA approves a sponsor’s IND, the sponsor may begin a Phase 1 clinical trial. This trial usually involves a small number of patients–between 20 and 80, depending on the nature of the drug and the condition it is intended to treat–and is focused primarily on safety, potential side effects, and how the drug is metabolized and excreted.

- Phase 2 Clinical Testing: If Phase 1 testing doesn’t find that a drug is unreasonably toxic, its sponsor can move on to Phase 2 clinical trials. These can involve hundreds of patients and are intended to demonstrate a drug’s effectiveness, often through comparison with a control.

- Phase 3 Clinical Testing: If Phase 2 testing demonstrates that a drug is effective against a condition for a certain population, sponsors and FDA officials meet to discuss how a Phase 3 trial should be conducted in order to demonstrate sufficient safety and effectiveness for approval. Phase 3 clinical trials are the largest, generally involving hundreds to thousands of patients. In addition to safety and effectiveness, these trials gather information on appropriate dosing, interactions with other chemicals, and the drug’s impact on different populations.

- Review Meeting: FDA officials meet with sponsors to discuss post-market or commitment studies that sponsors might be required to conduct in order gather additional information about drug safety, effectiveness, or optimal use.

- New Drug Application: Having completed Phase 3 trials, a sponsor submits a New Drug Application, or NDA (a Biologics License Application, or BLA, in the case of biological medical products), formally requesting FDA approval for their drug. This application includes all testing data as well as chemical and manufacturing information.

- Application Filing: Once an NDA has been submitted, the FDA has 60 days to decide whether or not to file it, opening it for review. The FDA may refuse to file an application if it is incomplete.

- Application Review: Assuming it has been filed, the NDA is now reviewed by FDA officials to determine the drug’s safety and effectiveness. The FDA aims to review and act upon NDAs within 10 months (or six months if the drug has received the priority review designation.) In some cases involving drugs intended to treat cancer, the FDA will convene a meeting of the Oncologic Drugs Advisory Committee, or ODAC, to make recommendations.

- Drug Labeling: The FDA examines a sponsor’s labeling to ensure that safe, accurate information about the drug’s appropriate use is communicated to patients and healthcare providers.

- Facility Inspection: The FDA inspects the facilities where a drug will be manufactured in order to ensure that the drug can be safely produced.

- Approval: Depending on their findings following NDA submission, the FDA will either approve the application or issue a complete response letter outlining their decision.

Once a drug has been approved, sponsors are often responsible for additional post-market research to confirm their drug’s safety, effectiveness, and optimal use.

At every step, ineffective or unsafe drugs are removed from FDA consideration. It is estimated that only 20% of drugs to receive Phase 1 testing end up reaching the market.

Graphic Courtesy of the American Association of Cancer Research2011 Cancer Progress Report[/caption]

Graphic Courtesy of the American Association of Cancer Research2011 Cancer Progress Report[/caption]